The Swarm, by Sylvia Plath - A Storming Dive into the Effects and Disillusionment of War

Poetry Criticism/Analysis

Opening

The twelve-stanza poem “The Swarm” by Sylvia Plath is a piece of creative writing that slips and slides sensuously across the eyes and ears, as much as it bites back and strangles the conscience. It is found in a thinner and more watered down collection of her poems called Winter Trees. They were all written in the last nine month’s of Sylvia Plath’s life, and form part of the group from which the Ariel poems were chosen. Most of them aptly demonstrate Plath in the prime of her poetic powers, displaying the stark imagery and references to chaos, religiosity, spirts, Western warfare, family building and linking, and deterioration. Ultimately, the collection displays on the frosting cream pages the pungent noun phrases, linguistic formulas of alliteration, repetition, and cuttingly sharp wordplay for which she became known.

Nearly all of the poems in the collection have a daringly indignant tone, stating clear-cut, physical phrases of anatomy, mention of a person or a part of their body that is crucial or startling in some way, adding to short and sharp narratives of human nature, the individual’s propensity for combat and violence, contrasted briefly against the solace, as well as the horror of the natural world. The immensely visceral Stopped Dead pulses off the page in the opening two lines: ‘A squeal of brakes. | Or is it a birth cry?’1, continuing to call out helplessly to family members, prominent literary characters from the past: ‘Uncle? Uncle? | Sad Hamlet with a knife? | Where do you stash your life?’ Ending in the last stanza with an echoing of natural materials and some semblance of the familiar: ‘Is it a penny, a pearl – | Your soul, your soul?’2

Objects and events in the poems appear to take on a humanely painful quality, while also being strangely suffocating, as with the compelling opening lines of The Rabbit Catcher: ‘It was a place of force – | The wind gagging my mouth with my own blown hair,’3; an opening couple of letters, swirls, and grammatical choices (most prominently the line-break) written ingeniously with Plath’s pen, once again subsuming the reader into a funnelled realm or place of a supernatural quality, a “force”, yet aggressively juxtaposed with a natural element of the earth “gagging” the speaker with a generally harmless part of the human body (“my own blown hair”). There are further connotations and feelings of being constricted and swallowed: ‘There was only one place to get to. | The paths narrowed into the hollow. | Zeroes, shutting on nothing, | Set close, like birth pangs.’4 The speaker concludes the poetical diatribe-of-sorts describing rather mundane yet eerily dangerous objects absorbing her sense of self and her loved one: ‘And we, too, had a relationship – | Tight wires between us, | Pegs too deep to uproot, and a mind like a ring | Sliding shut on some quick thing, | The constriction killing me also.’5 Close human interaction and suffering, months and years of sowing love seeds, and “Pegs too deep to uproot”, all evoke emotive and piercing ideas of family relationships being attempted to be built, yet in the end are descending and being fractured by human acts of will, and the self being prone to destruction.

While not as emotionally, or domestically close to the human heart as the aforementioned works in the collection, The Swarm is equally, if not more physically lurid and intense. First, in its construction; the all too deliberate subject and verb phrases marking out a specific person, the mention of much larger and significant military names and battles, the cutting-off from individual lines; and the historical and geographical weight that whole lines and stanzas evoke. In The Swarm, Plath minutely crafts together a storming human poem harking to local and natural scenery, filled with grit and weaponry, whose bark is as loud as its bite – and there is indeed multiple mention of dogs.

The Opening Line

The opening line is a direct alliterative follow-on from the title; it mirrors it with the thrice repetition of “s”, providing the immediate sibilance and sonorous sounds on our conscience and tongue, shaking us into shape for a strong and unexpected poetic journey. The only clear difference is the lack of a determiner at the very start of the phrase: ‘Somebody is shooting at something in our town –’6

As a consequence of Plath using the pronoun “somebody”, she cannot – according to strict grammar – begin the opening line with “the” (even though it would be acceptable in poetic composition). An “A” preceding the pronoun would suffice, although “A Somebody” does lend to sounding somewhat vague and grammatically askew. The word “somebody” is an indefinite pronoun, which typically does not require a determiner to precede it. However, in certain contexts, quantifiers, which are a type of determiner, can be used to indicate an unspecified quantity or number. Therefore, you might say “almost somebody” to suggest nearly anyone, or “such somebody” to imply a person of a certain kind. But generally, “somebody” is commonly used on its own without needing a preceding determiner. Without becoming grammatically authoritarian and excessive, Plath, we can assume opted to stick to syntactical type, and introduces the initially unknown “somebody” in darting, out-of-the-blue fashion. From the title we can infer that we will be plunged into a sudden burst or frenzy of words that convey a sense of chaos, mayhem, some sort of storm, perhaps. With the deliberate alliteration of “s” continuing aggressively, almost violently, first with the present participle “shooting”, then verifying that the somebody is firing “at something”. Thus, for all the craze and peril we extract from the beginning, we are perhaps minorly comforted by Plath declaring that this person is shooting at a designated object or target, which is essentially what the practice of shooting entails; although since the title “The Swarm” evokes ideas of a crowded group, or large herd of people or objects, it would arguably not have been surprising if Plath had written the “somebody” shooting frantically into the air above, below, or in some crazy circularity; as beleaguered radicals/terror suspects are sometimes depicted doing at climaxes of a thriller episode on television or film when they have been found out, and revert from their initial egregious intentions of shooting down and killing innocent individuals. Plath concludes the line with “in our town –”, which pins down and signifies that these initial harrowing and visceral events are taking place at a local level. Attempting to extract specific locational context here is difficult; the “Winter Trees” collection as a whole was written during the last nine months of her life, and it is known that Sylvia Plath spent her last years in the United Kingdom, particularly in London and Devon. Given the timeline, it is likely that these poems, and the conclusion of this opening line in The Swarm, is being written during her time in these locations, providing a powerful reflection of what she sees, witnesses, and takes in whilst residing in the more secluded country, as well as her intense personal experiences and emotional states. Specifically where this “town” is, we cannot accurately conclude, although given that Plath chooses to use the geographical marker of a “town”, this could potentially mean that she is referring to a smaller, more localised community in the English country, perhaps in Devon. For the British do not necessarily denote there being “towns” within the greater city swarm of London; there are boroughs, and lots and lots of smaller named communities (Aldgate East, Bloomsbury, Piccadilly, Kensington, etc.), but “towns” are not commonly referred to by veteran Londoners themselves. Finally, the long dash, “–”, is a cleverly effective grammatical devise used by Plath at the conclusion of the overtly long opening line, for it can be argued to act, somewhat poignantly, as the line of fire from “somebody’s” arms, or whatever firearm they are holding. The dash, or line, marks and emphasises the introductory line itself as the fierce declarative phrase that it is; the speaker announcing that a person is shooting at something in a real place, and we receive the visual blow and specification from Plath via the symbol at the end: “in our town – …” like a line of gunfire itself, leaving us the reader somewhat shaken, jolted off our equilibrium, and curiously wondering what we will uncover in the following lines of this jarringly sensory poem.

Getting into the Groove

The next line and flow into the first stanza contain an unsurprising sequence yet succeeds in maintaining the dangerous and restlessly kinetic underlying aura: ‘A dull pom, pom in the Sunday street…”7 Plath “dully”, somewhat ironically describes the “shooting” from this person as being a “a dull pom, pom”, which is a surprising way to describe gunfire, and dually unsurprising. For to describe gunfire in a town as “dull” kind of evades the entire meaning of gunfire itself; gunfire evokes feelings of danger, harm, panic, potential fatality, therefore Plath opting to describe it as “dull” appears on the surface to be ostensibly disregarding the appropriate humane response to gunfire. Vis a vis, why is Plath not following her opening line with quotes from passersby in the town screaming “Get away! Get away! Gunfire! Gunfire!”? Then again, we can make room for Plath’s seemingly nonchalant description of the gunfire itself; conceivably, after so many bullets fired, harm done, and blood spilled, at the end of it does the gunfire turn out to just be the expected background noise that precedes all the casualties and injuries? Is gunfire a “dull” sound when we hear it continuously and morosely for a period of time? The fact that by large probability, and that it has the propensity to take lives (both human and otherwise), is it the dull outcome we expect to happen when tragedy is forecast, or nearby? Perhaps so, and very much likely so the case for Plath here.

The onomatopoeic “pom, pom” is written to sound quite comical, almost juvenile, bringing to mind the sound of children making the high-pitched “play” noises of gunfire when playing with their friends. Then, bringing in the timestamp and location of it happening “in the Sunday street…” carries a multiplicity of deeper meanings and poetic invocations from Plath; “Sunday” denotes clear references to the Church, religion, pious people attending their local Church in this “town”, while also likely emphasising Plath’s personal religious beliefs, or lack thereof; Slyvia Plath was raised as a Unitarian when growing up in Boston, although experienced a loss of faith when her father passed away, and thus remained ambivalent about religion throughout the rest of her life. The noun phrase concluding with it being on a “street” both links tightly with the Sunday reference to churchgoing; invoking images of grey and brown brickwork, tarmac roads, alleys and segmented roads that lead to places of worship; and directly contrasts the more abstract concept of “Sunday”, which is a social term of time that humans have invented to mark a day in the week where people typically have a day off of work or school, yet the “street” is concrete, both physically and metaphorically; it is usually a place containing a long road or segment of rock hard, solid ground, and a definite place that contains “something” humanly manmade, whether it be homes, residences, shops, places of commerce, perhaps even chapels and churches. Thus, this radical “somebody” emitting gunfire on a “Sunday street” mirrors the brutal, hard nature of the events introduced, whilst vehemently juxtaposing the more peaceful elements to happenings in a town on Sunday, including Church attendees and services.

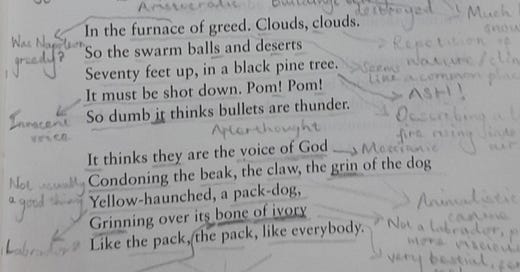

The final three lines to the opening stanza are all equally profound, both in their metrical weight, and literarily in the links they make to the preceding lines and the connotations given off by Plath. Similar in length, going from eight syllables in the third line, to six syllables in the fourth and fifth: ‘Jealousy can open the blood, | It can make black roses. | Who are they shooting at?’8 As a literary sidenote, Plath introducing the social concept of “jealousy” gives powerful undertones to historical pieces of literature, particularly the Shakespearian play of ‘Othello’; the protagonist opting to take a grand and angry vendetta on one of his best friends and eventually his wife after being supplanted with false claims and ideas about his wife’s infidelity; arguably the most profound line from the entire play being a direct metaphorical reference to jealousy itself: “Oh, beware, my lord, of jealousy! It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock The meat it feeds on”. The possibility of the often detrimental human emotion (jealousy) “opening the blood” is possibly Plath referencing this somebody on his/her/their shooting spree, both the barer of the arms themself and those they are firing at; thus the blood is open and more likely to spill and drain from harm from the firearm; this somebody is fuelled by jealousy for an unspecified reason, and while it is not a certainty that severe harm will be done, it certainly can do a good deal of human damage. “It can make black roses…” is an incredibly dark and baroque declaration from the “blood opening”; perhaps being an allusion to potential blood spill from people who have been shot and severely harmed; consequently, other innocent people leave roses for the dying as a sign of love and respect, but all the dark blood spillage and viscous liquid taints the “red” rose, possibly leading to it turning “black”. Then, after this patently dark couplet alluding to the redness of blood and roses, Plath’s speaker virtually snaps out of their deep, gothic, metaphorical guise, and suddenly becomes concerned for the targets or victims being shot at; adopting a sharp interrogative phrase to close the opening stanza: “Who are they shooting at?”, which we can hear Plath’s speaker asking loudly and forcefully, with particular stress on the modal verb “are”, so it would be voiced in this kind of vein: “Yes, who are they shooting at?” All of these poetic devices – shifts in phonetics (from “s” to “p”, “j” to “b”), a gradual decreasing in syllable count, clear imagery of gunfire, deliberate use of grammatical symbols, a breaking down of thematic elements to jealousy – make this opening stanza a construction of artful quality, providing the disordered foundation offered to the reader for a poem that is at its heart fuelled by chaos; havoc; a surplus of harmful and perilous activity happening within Plath’s world.

Into the Heart of the Swarm

In the second stanza, Plath provides some answers to her initial statements and musings from the first, though they are less gratifying to uncover and read than they provide a destructive feeling of immediacy and danger, upholding the severe threat and imagery of gunfire and battle. She addresses the reader directly and says: ‘It is you the knives are out for…’9, which provides a couple of deeply intriguing shifts in tone and object. From the very ambiguous opening line where characters and culprits are not specified, but left anonymous and vague (“Somebody is shooting at something”), Plath swings the poetic narrative into strong motion and incites a palpable sense of fear into the reader (or so that is her intention), in essence writing that we subsume the targets of the gunfire in the poem. Plath’s choice of addressing us suddenly in the second-person (“you”) is a striking turn by Plath as we enter the crux of the poem (the “you” being a commonly powerful narrative device utilised by writers to emphasise a stronger perception of identity with the reader, as if we are living the story itself). “the knives are out for” us, therefore we clarify that we are the targets in the narrative, threatened with weaponry and potential death; the idiom “knives out” being used deftly and subtly by Plath, referring to us directly and saying the “somebody”, the people with weapons are aggressors against us; “we” are the enemy to be hunted; whilst the inference of “knives” adds an extra volume of sharpness and severe hazard, paralleling the previous stanza with the mention of blood and roses, and the potential for knives to draw blood and create a spillage of red, multiplying the harrowing feeling of threat, fatality, even sorrow.

Plath uses a smart enjambement to lead into the second line of the stanza: ‘… At Waterloo, Waterloo, Napoleon,’10 clarifying that the weapons are firing in a particular setting, still targeted at us, though forces us to trace back through history to the infamous Battle of Waterloo. Plath marks a turning point in the poem where a clear historical reference is induced and made visible to us; to Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars, particularly the Battle of Waterloo, the second bloodiest single day battle of the Napoleonic Wars (after Borodino). Even though this particular battle marked Napoleon’s eventual defeat to the Coalition of European Nations who opposed him, and eventually his ultimate abdication and ended the First French Empire, we are still thrown into the midst of one of the deadliest military battles in recent Western history; we as the culprits and targets of the gunfire, the ones “the knives are out for”, are not only in patent danger in this great societal battle, but plunged into a grand and vacuous area of pastoral land (Waterloo being part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands at the time, now part of current-day Belgium), throwing up images of vast, interminable fields ahead, huts, military support units, red cotton coats, and bayonets; in essence, Plath plummeting us into the field of battle and making us the enemy; though compensates us somewhat in taking us back in time to an historical battle, where we may have a chance to “run around for a little while”, gather up some resources and protect ourselves. It is notable how Plath cleverly mirrors the repetition in this second line of stanza two with the second line of stanza one: “At Waterloo, Waterloo…” | “A dull pom, pom…”, so we feel not only the dulled weight of the gunfire, but makes us consolidate that we are now in the setting of the old location of the British Empire; in other words, Plath very much wants us to feel the weight of warfare by dropping us firmly in this destructive and potentially fatal place. The final three lines of the second stanza deliberately undulate in syllable length, initially increasing, until finally reverting back to a characteristic short length by the close: “The hump of Elba on your short back, | And the snow, marshalling its brilliant cutlery | Mass after mass, saying Shh!”11. The third line is a deliberate continuation of the grand military ruler Napoleon Bonaparte, as we the readers and Napoleon morph into the designated target to be attacked, with “The hump of Elba” being a direct allusion to Napoleon leaving the Italian Principality of Elba, which he ruled for ten months before escaping to Southern France, which marked the beginning of the Hundred Days (a period that ended with his final defeat at Waterloo). Therefore this “hump” is Plath anthropomorphising a specific period in which Napoleon experienced difficulty during his premiership, being on a rather remote European island where the rest of mainland Europe are relatively free from a potential militaristic attack from the Emperor. Additionally, Napoleon’s “short back” that carries the burden of this period becomes our own back: “on your short back”, so we take up the role of a military leader who has the weight of many years of travelling cross-continent, fighting in and winning battles, though somewhat stumped and weakened; Napoleon is characteristically known for being rather short in height (many scholars agree he was around 5’6’’, which was not shorter than the average Frenchman at the time). The fourth line of the second stanza is a magical piece of prosody from Plath that metamorphosises a significant part of the climate and nature: ‘And the snow, marshalling its brilliant cutlery’, carrying an enchanting duality of meaning; first how it personifies the snow as “marshalling” which alludes to the large country area of Waterloo being covered at certain areas with snow and being marshalled in the sense of it being used for posts and spots for military purpose, with the “cutlery” almost certainly being chosen as the sharp image Plath intends to create in our mind of glossy, metallic objects (knives, bayonets, swords) being used across this vast area of land; second, how the snow can be humanised and described as “marshalling” itself, the cold, white surface rearranging in the wind, shuffling and undulating as the weather changes throughout the day, blowing and travelling far and wide throughout the night; hence, the snow’s “cutlery” in this sense may be the snow’s freezing cold composition, its disposition being a sharp coldness that is quick to bite and cool an animal’s skin, that can sting a human hand if held for too long without warming protection. Plath concludes the stanza with the almost yelping: ‘Mass after mass, saying Shh!’; we are once again thrusted back into this swarming military mayhem, multiple “masses” fighting and firing on enemy lines and doing their utmost to defeat the enemy, while we also get a robust reasserting of this grand imagery of vast swathes of snow, “mass after mass” of it merely desiring to be left at peace in the immense European landscape, therefore Plath intends for it to humanised by reverting to speech: “saying Shh!”

The third stanza is a clear continuation of the snow attempting to quiet down the chaotic warfare: ‘Shh! These are chess people you play with,’12 which is possibly the snow giving out a second drastic warning to us (now apparently sided with Napoleon), and that the enemies we are fighting are “chess people”, thus are very tough opponents to beat, with “chess” being the smarting noun that infers feelings of challenge, tactics, strategy, which are often key tenets when it comes to trying to better and overpower opponents in the battlefield. Plath then closes the second line of the third stanza with a firm full stop after the solid four-word phrase: ‘Still figures of ivory.’13 This vocabulary choice of Plath to use nouns that evince extremely hard and firm materials – of which “ivory” is a strong material extracted from elephant tusks and was prominently used by the Greeks and Romans for sculpting and works of art – confirms in our mind that our opponents in this battle (likely the Coalition Armies against Napoleon and France) are almost definitely experts, emphasising their astute ability and depth in arms. Consequently, we can theorise that the large natural body of the snow, remaining personified telling us to “Shh!”, is moreover a subtle call for us to put down our weapons sooner rather than later, as this current war to try and topple the British, Dutch, Prussian is going to be anything but a walkover; they are seasoned customers who have great history and practice in military war, and being teamed together this makes them an even tougher opponent to beat. Although we seemingly cannot resign, for we read on with Plath’s combative words, stuck in the battlefield; she throws us back into the apex, or middle of the battle itself, bringing in more earthly and visceral descriptions to accentuate the gloomy grit and damage done in human battles: ‘The mud squirms with throats,’14 is an especially grimy and grotesque image filled with onomatopoeic sounds of the “squirming” of the “throats”, a filthy and harrowing convergence of the earth and the human body when people are left to be killed and trampled on when they succumb to their injuries in the field. Then, it is perhaps Plath’s narrative voice coming through and quietly being echoed at this key moment in the poem; a silent hazardous call from her as she has already informed us that our opponents are as solid as “ivory”, so the “mud squirming with throats” is a pungent line that darts in on us to remind us what could happen if continue to fight in this anarchic battle. To continue with this disturbing imagery, the human casualties eventually become: ‘Stepping stones for French bootsoles.’15 In essence, the large portion of enemies that have been conquered and lie on the ground with “mud” and “throats” abound, provides the literal “platform” for the French to advance and make up ground on whilst they look forward to their next target; the “Stepping stones” and “bootsoles” being particularly choice words used by Plath to stress the battle-hardened, serious, marching element to how military battles operate. The third stanza finishes with one of the longest lines of the entire poem, which is demarcated from the rest of the stanza, acting as an enjambement that leads into the fourth stanza; the line provides a temporary easing of the fatal disturbing images we have been shown, yet still evokes a strong senses of things collapsing and being defeated: ‘The gilt and pink domes of Russia melt and float off…’16 “The gilt and pink domes of Russia” is rather conspicuous language from Plath, yet brings in a great array of historical references to the Russian Empire; the Russian Empire itself was one of the dominant powers in Europe in 1815, especially after playing a significant role in the defeat of Napoleon in the Battle of Waterloo. Following Napoleon’s defeat, the major continental event of the Congress of Vienna took place, which included Russia, where the European powers redrew the map of Europe. As a result, the Russian Empire managed to expand its territories to include Poland and Finland. To a more political end, the “gilt and pink domes” Plath suggests falls very much in line with the governmental make-up of the Russian Empire at the time, which was an absolute monarchy, with the Emperor having considerable power over proceedings, although this was somewhat limited by the extraordinary size of the country and the administrative systems in place. The monarchical element to the Empire chiefly evokes ideas of aristocratic, upper-class lifestyles; the “gilt” would likely refer to the minutely-patterned, gold-framing of many portraits and paintings that adorned the grand walls of Russian palaces and residences, and the “pink domes” would undoubtedly be Plath alluding to St Basil’s Cathedral, located in Red Square, Moscow; the cathedral is famous for its colourful, onion-shaped domes, and one of them features a vibrant pink colour with golden patterns; no doubt it is a famous symbol of Russia and a key attraction for visitors from around the world. Yet, for all the allure and grandness of Plath bringing in these opulent pieces of Russian design and architecture, she decides to describe them “melting” and “floating off”, which could mean that Napoleon has already done a great amount of damage to these iconic buildings out of anger, possibly avenging the loss of many of his French troops to the Russian army, and moreover his desire for supreme power over Europe and beyond. As we traverse into stanza four, we indeed discover just how and why the “melting” and “floating off” is taking place.

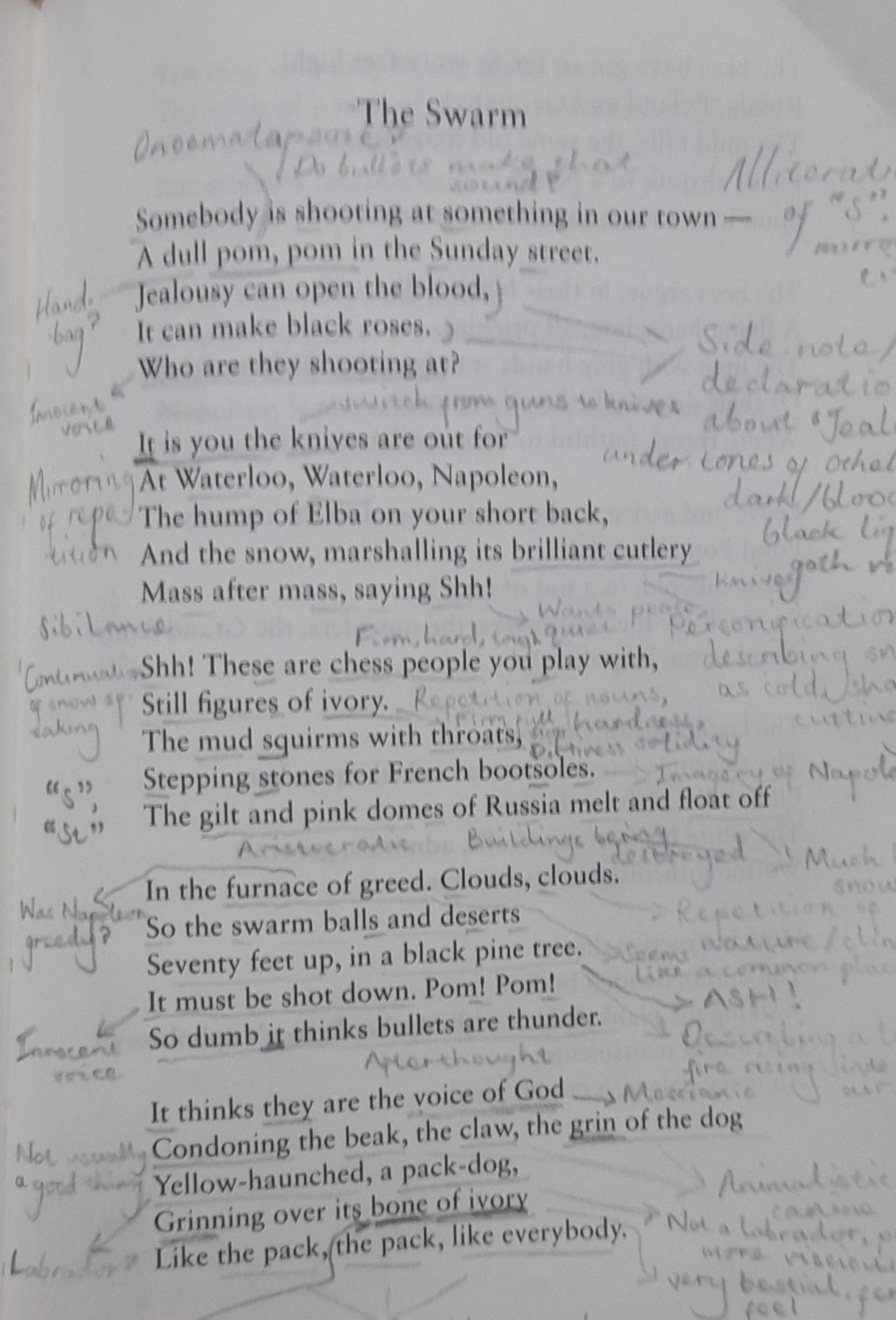

This Russian disaster is taking place in “the furnace of greed”, an unsurprising literary phrasing of Plath, honing in on Napoleon’s power-hungry, psychopathic endeavours; although it likely refers back to the Fire of Moscow in 1812, which all but destroyed the former Russian capital of the time. It has historically come to be known as a strategic decision made by top Russian governors and military commanders, to deliberately burn most of Moscow’s resources by scorching the earth; this kind of war without major battles weakened Napoleon’s French army at its most vulnerable point during their occupation of Moscow. By October 1812 the French army, lacking provisions, and being warned by the first snow, eventually abandoned the city voluntarily. Having said this, the more general idea of a mass fire on this scale chiefly connotates significant feelings of conquered and beaten places, a turning over of power, destruction of land, and a dictator forebodingly maintaining his despotic rule over large areas. The full first line of the fourth stanza is written: ‘In the furnace of greed. Clouds, clouds.’17 The “melting” and “floating off” of buildings and composite materials is the banal outcome we expect in a huge fire, although the fact it is a “furnace of greed” would mean it is not a minor, or accidental burning, it is very much substantial and intended to cause disorder and dread; the very idea of our own house burning down and melting to ash is a scenario that none of us wants to transpire; although sometimes acts of arson are done by certain individuals with ulterior motives; sometimes they are instigated by unintended, minute things, yet unlikely tragedies such as large buildings burning do take place in the urban world. The “Clouds, clouds…” concluding the line is a thoughtfully written composition by Plath, repeating the word to highlight that even though we are entombed in an anarchic and deathly world in the poem, it is still important for her to indicate how nature plays its part in the events; that battles are won and lost by people, but the land and grass continues to grow and remain. The small phrase also signifies the foreboding, gloomy nature of fires and burning, almost as if a volcano eruption has taken place, with grand, dark clouds of ash rising and formulating in the sky above. Plath continues: ‘So the swarm balls and deserts | Seventy feet up, in a black pine tree.’18 She allows us to find out what “the swarm” entails rather early on in the poem, coming in conspicuously amidst the imagery of destruction and war, in the heart of the battlefield. We can conclude this “swarm” that is haunting the words, the nature, and the poesy itself, is Plath directly pointing toward the very idea of war and the consequences that come from it; it may seem like a “swarm” that people are lost in at the time, humans defending and fighting for their country, perhaps rightly so, but why create this swarm initially? Look at the blood spilled and number of fatalities. Plath describes it forcefully “balling” and “deserting”; hot air rising “Seventy feet up, in a black pine tree.” This almost acts as the fatal culmination, or climatic point for us to briefly take off our lens of being within the war of the poem, and reaffirm our view as a neutral, passive reader; we should look at the burning and bloodshed, the “mud, throats, stones, bootsoles, furnace etc.” and see how awfully bad things are at this moment. The dark smoke from the fire branching out into the sky and forming a “black pine tree”. It almost emanates imagery from Francis Ford Coppola’s highly acclaimed Vietnam War movie Apocalypse Now (1979), the scenes when Captain Willard transfers to Lt. Col. Bill Kilgore’s fleet, firing forcefully at local Vietnamese villages, flame-throwers abound on ground-level, and the widespread burning and destruction within the greater swarm of the gigantic pine trees and bushes of the Vietnamese jungle. Plath resorts to taking on a briefly comical tone in the final two lines of the stanza: ‘It must be shot down. Pom! Pom! | So dumb it thinks bullets are thunder.’19 Initially this echoes Plath’s former line of an innocent voice suddenly darting in (“Who are they shooting at?”) and commenting on events, declaring what they think should happen according to human logic. It takes on the feeling of a shocked child yelling, as they can clearly see all the irrational destruction taking place, the “Pom! Pom!” a clearer and harsher recital of the former onomatopoeia used in the first stanza (“pom, pom”), now being used as a yelping call, acting as the imagined guns being fired to try and alleviate the damage and take down the real enemy. The final line comes off as more of a funny afterthought from Plath, going back to a side-commentary of the events occurring: “So dumb it thinks bullets are thunder.” The “it” here is likely referring to us once more on Napoleon’s side, right back in the thick of the action, therefore as we lose ourselves in the constant gun-fighting and ceaseless burning we become so absorbed in the battle that we hear random gunfire in the distance as “thunder”; in Plath’s swarm, we do not really get to see good and noble actions for what they really are; they are part and parcel of our mission to defeat the enemy with our weapons, to cause more demise and devastation.

At the culmination of the first page in the fifth stanza, Plath invokes a surfeit of animalistic, beast-like imagery to consolidate the profound physicality, the geographical element to human battle, along with the addition of venereal creatures and human pets, being an at times vital counterpart to individual’s when they lack fellow human company beside them. She begins the stanza with the mention of the modal pronoun “It”, referring again to ourselves having joined Napoleon’s army, fighting beside a militaristic tyrant fuelled by political greed and supreme arrogance: ‘It thinks they are the voice of God…’20 A bold statement, almost claim, presupposing that us having combined forces with the French ruler, we instantly occupy hugely inflated opinions of ourselves and our martial abilities; to the point that we regard ourselves as an all-powerful, messianic figure; being combined with Napoleon and his forces we are almost automatically endowed with morals and abilities that are omnipotent, ultimate, and final. The immediate linguistic switch from Plath to refer to us as “It”, then through our quick thinking and stream-of-consciousness we become “they” (“It thinks they…”) is an acutely clever shift in narrative viewpoint to once more give emphasis to the fact that we are part of a large group of troops at battle; even though we initially feel the lonesomeness and lead-like weight of being by ourselves on the battlefield, it is crucial that we are constantly surrounded by plenty of other members of the army, who blindly and dully uphold the despotic vanity of the Emperor Napoleon. Because we are fervently described as thinking we are “the voice of God”, Plath maintains our arrogant holiness, our unique abilities that we think we possess, going on to write: ‘Condoning the beak, the claw, the grin of the dog | Yellow-haunched, a pack dog, | Grinning over its bone of ivory | Like the pack, the pack, like everybody.’21 Instantly we realise that we are not necessarily good, or moral with our holy actions; we “condone”, which is to say that we give allowance to things usually deemed immoral; “the beak, the claw, the grin of the dog…” is a quietly ingenious use of abecedary language from Plath, as we go from “b” to “c” to “g” (“beak”, “claw”, “grin”), forming an alphabetical triad of bestial imagery, being the hard and tough animal-like objects and behaviours that we are making acceptance for; essentially, they violently coalesce, and could well be metaphors for the military weapons we are using, as well as representing the intuitive behaviours that we adopt when we are fighting enemies and trying to survive ourselves; beak-and-claw-like, “grinning” in sadistic fashion when we succeed in gaining minor triumphs. Yet, Plath absolutely intends to keep the canine imagery alive within the poetic narrative, magnifying the lurid anatomy of dogs, “Yellow-haunched, a pack dog,” which brings to our eyes images of well-cut, dark, and golden-furred canines stationed at particular points, roaming around seeking to claim territory; the “haunch” being the meaty, bulbous backsides that they carry, while clarifying it as “a pack dog” draws our attention to fast and alert dogs that are part of a well-formed group or legion, ready to pounce on a certain command from an owner. More than anything, the excess Plath writes in at this point of animal features and behaviours – “beak”, “claw”, “Yellow-haunch”, – is undoubtedly intended to strike fear and panic into our opponent’s eyes within the battle; the abundance of brutish and dangerous bodily features is a violent option we have at our disposal if we feel in need to use it. The conclusion to the stanza hones in further on this sadistic element to the fighting and killing: “Grinning over its bone of ivory”, which is a significantly astute metaphorical shift from Plath in melding us within the vantage point of the pack dog itself; we are “grinning” over a “bone of ivory”, arrogantly pleased at standing over a dead body, a defeated enemy that will soon become hard with rigor mortis, becoming a hard “ivory” object, and we smile over it sadistically in the vein of a Dracula-like villain, adding a touch of brooding Gothicism to the piece. Eventually, we join up once more with our fellow troops and the rest of the military fleet: ‘Like the pack, the pack, like everybody.’ Plath wants to make the brutal nature of human warfare and destruction absolutely clear and prescient; the conformism of large societal groups accepting and being part of the immoral killing and cleansing of a fellow group of human beings. From the more playful metaphor of “pack dogs”, we eventually transmute back to the ordinary custom of humans living passively in abundance in packs themselves, accepting our place and our current vocation, perhaps realising that it could well be the wrong thing to do, but we are too passive and weak to speak up or turn back on ourselves, thus we just become “like everybody”, almost like staffage drawings by architects, adding small human figures to architectural sketches and paintings, who merely become passive observers in society and do not truly realise their place or what they are part of.

Part of the Beehive

As we embark into the sixth stanza we are shot with images of “bees”, who denote the over-abundance, swarm-like element to the chaos of warfare: ‘The bees have got so far. Seventy feet high!’22 Having already been thrust and become key players in this great Napoleonic battle, the natural aura and more calming aspect of a large group of “bees” provides a heroic introduction of troops that are humanised and act as our noble opponents in the battle itself. Their fleet rising “Seventy feet high!” is exclaimed purposefully by Plath to demonstrate their travelling number; tiny in their individuality, but enormous as part of a group, that rise up to the height of the dark, burning “clouds” of the “black pine tree”. We are then made certain of their allegiance and what side they are fighting on, as Plath makes a direct historical reference to the nations who are fighting against Napoleon: ‘Russia, Poland, and Germany!’23 This repetition of a linguistic triad harks back to the “beak, claw, grin of the dog”, except it is starkly reversed from its initial evil connotations, forming the alliance of national coalitions and groups that aim to stop Napoleon’s autocratic threat of ruling Europe. Even though Poland would eventually become a part of the Russian Empire after the battle, Plath intends to use all the vital areas and countries, predominantly eastwards, that were all a part of the political resistance to Napoleon’s French Empire. The intentional highlighting with the conjunction “and Germany!” is a near-ironic reference from Plath, as while the nation at the time very much opposed Napoleon’s army, in recent history they have become a staple for radicalism and harsh political division (particularly Hitler’s regime, the Holocaust, and the divide between Eastern and Western ideals), consequently Plath brings out of the contradiction of morals of Germany a new contradiction of radical nobleness and truth; they are fighting with Russia, Poland, and the rest of the coalition against Napoleon, therefore are supposedly “on the right side of the fight”. Plath then fluidly ventures back to the harsh and large natural imagery of the pastoral surroundings, closing the stanza with a more foreboding and dim view of proceedings as we, along with the “bees”, are still patently taking part in the blood-spill of this great war: ‘The mild hills, the same old magenta | Fields shrunk to a penny | Spun into a river, the river crossed.’24 “The mild hills” being “the same old magenta” seems to be an intentional imbuing of colour from Plath, as the colour of “magenta” is a purplish-red, falling halfway between violet and red, so acts as a sort of bridging between the redness of all the blood spilled and the roses laid on the dead, and the more herbaceous colour of violet, which denotes more peaceful images of flower petals and calming fields untainted by grazing and violence; also acting as a subtle sub-reference to the bees, as they tend to pollinate on the petals of violet plants in more temperate climates. Unfortunately, as the fields have now been “Shrunk to a penny”, which is a wide-reaching reference to all the trampled on plants and flora, dismissed and disregarded by the gilt-buttoned, coated soldiers killing each other for the cause of national honour. Plath expertly closes the stanza with the personifying of the “penny”, an enjambement that leads into it being “Spun” – much like a coin is when it topples onto the ground and circles repetitively on its thin edge before falling on its side – “into a river”, as the aforementioned land of snow and bog and grass travels and fades into water flows and streams in the surroundings, before being “crossed” sullenly by all the soldiers to get to the next checkpoint of the battle.

“The bees argue, in their black ball,”25 Plath writes to open stanza seven, as we scarcely need a harsh focal lens to identify the repetition of “The bees”. They are seemingly now in prime activity, “arguing” in “their black ball” as Plath severely severs the yellow part of their hazardously-coloured-make-up, now having fused with the “black pine tree” and become a muddled “swarm” themselves, bickering amongst each other as to whether all their hard-fought battling and harrying is worth it or not. They become in Plath’s words: ‘A flying hedgehog, all prickles.’26 We receive a signification of the sharpness and spikiness of certain animals and insects figuratively taking the place of humans who bear arms, holding sharp and piercing weapons that have the power to hurt an opponent with great pain. The “prickles” themselves are almost certainly symbolic of the harsh weaponry possessed and utilised during the Battle of Waterloo; muskets firing bullets, opponents defending themselves with bayonets, officers carrying swords in side-pockets and satchels, as well as some sergeants carrying a half pike, or ‘spontoon’, which gravely harks back to the weaponry used in Medieval days. The metamorphosis of bees forming a “black ball”, to a “flying hedgehog”, and finally to mere waving strands and “prickles” is an efficient literary transition that Plath uses to underline the intensity of an extreme multitude of soldiers and officers joining the battlefield and losing themselves in the murky melee of the warfare. Plath writes in another extended line of twelve syllables, and a further two more of medium length to accentuate and summarise the feel of a huge beehive bombarding and occupying themselves: ‘The man with grey hands stands under the honeycomb | Of their dream, the hived station | Where trains, faithful to their steel arcs,’27 a richly deep and meaningful passage, absorbing and personalising the after effects of the bees trying to fight and work, yet succumbing to the tyrannical hands of the military oppressor; “The man with grey hands” merely “standing under honeycomb” illustrates a rather gloomy image of tall and senior sergeants standing by and waiting for more death to befall their opponents, part of a “dream” incorporated within the sweetly rich and opulent realm of “honeycomb”, as “the hived station” leaks and oozes honey; thus these “belligerent” bees act as the National “belligerents” of the war itself; the partakers who through their incessant fighting are causing ceaseless death, and in the end allow the honey to form and fall; becoming the expectedly sweet outcome that Napoleon desires. The concluding enjambement to “the hived station” is a place “Where trains” arrive, being “faithful to their steel arcs”, which represents a significant historical nod to the beginning of the era of industrialisation in Continental Europe; rampant patents and go-aheads given to the building of steam locomotives. It could very well be Plath directing her attention to her current residence in England, with the United Kingdom being one of the most vital players in the industrial boom in the nineteenth century, and seemingly an ever-present nation in key military battles in recent history; perhaps Britain is the most “faithful to their steel arcs” in Plath’s eyes.

Stanza eight begins with a direct enjambement from the last line of stanza seven: ‘Leave and arrive, and there is no end to the country.’28 This acts as a transition, a travelling transfer of power, where the industrial arrival and exit of “trains” appears to provide a crucial counterweight and shoulder for troops to embark, or disembark amongst the mayhem of the battle, and finally begin to topple Napoleon’s Grande Armée. The long and hard “steel arcs” from the previous stanza representing the far-reaching tracks that the trains motor on, arriving at important destinations, so that “there is no end to the country.” Plath abruptly introduces the innocent voice of opposing soldiers firing their guns again, repeating the onomatopoeia from the opening and fourth stanza: ‘Pom! Pom! They fall | Dismembered to a tod of ivory.’29 This is the seemingly key shift in the battle, where the Coalition forces are beginning to fire their artillery with greater force and fervour, increasing in number and believing that they can topple the dictatorial enemy. The enjambement from the second to the third line in this stanza is arguably the most historically and literarily meaningful, as Napoleon’s soldiers “falling | Dismembered” heeds back to the religious Fall of Christ, and the “dismembering” not being absolutely followed, but paying reference to the Holy Cross as Jesus’s limbs are tied and hung in unnatural human positions. Plath firmly capitalises “Dismembered” as part of the enjambement to emphasise the negative prefix of “Dis”, consequently highlighting the lack, or complete lack of “members” being fully formed and in place on the human body, thus they fall “to a tod of ivy”; becoming a clump of bushy mass of limbs piled atop each other. Following this poignantly primitive, biblical imagery, Plath writes in a distinctly long sixteen syllable line that jokingly mocks the grandness and expected triumph of Napoleon’s army finally beginning to collapse: ‘So much for the charioteers, the outriders, the Grand Army!’30 The once more triad of military resources, “charioteers”, “outriders”, and “Grand Army” are written next to each other in the long line, separated via commas, which presents these lavish vehicles of the day being placed beside each other figuratively as well as literally, stationed like horse-carts out in the country that are now being targeted for their vulnerability; the aristocratic vehicles becoming obsolete, for all their great design and function they are marshalled by animals thus have the propensity to be damaged and harmed to great effect. Plath closes the stanza with a sardonic military action which pays homage to the Grand Army of Napoleon now being bettered and overcome; a revered authoritarian leader’s large military falling to the Coalition nations: ‘A red tatter, Napoleon!’31

The Bees Have Victory

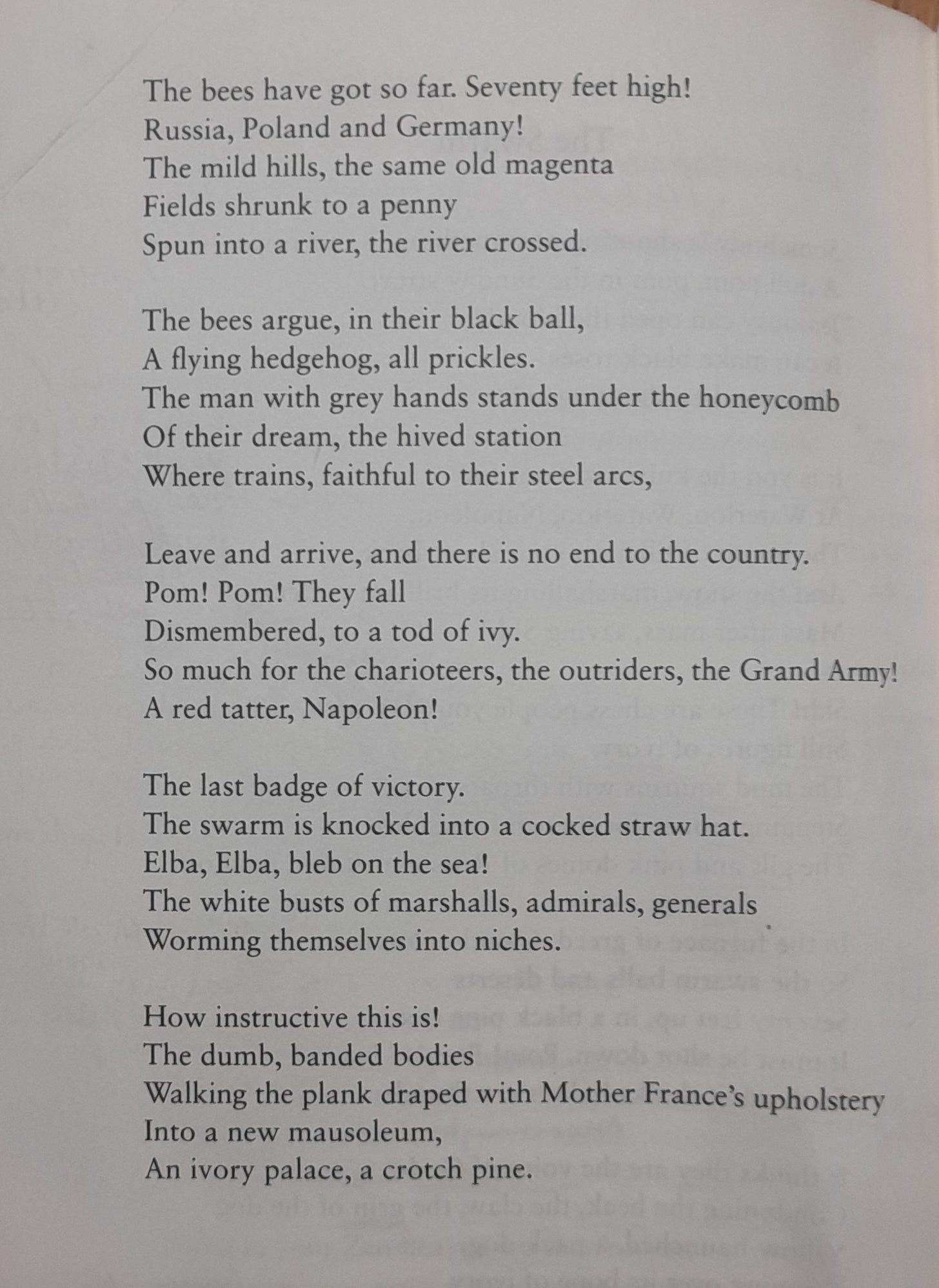

To begin stanza nine, Plath sustains the militaristic lingo to mark this segment within the Battle of Waterloo where Napoleon’s army is starting to crumble, hailing it as: ‘The last badge of victory.’32 To the avid militarist, this is a line that will resonate with them well, as they are acutely aware of how crucial particular triumphant moments are in an extensively arduous and long period in the battlefield. It is almost written to the degree of a budding Cub Scout gaining and receiving a badge for their efforts on a muddy assault course, at the completion of which they can expect to be given a badge to mark their accomplishment of the practical activity. At this point in the poem the narrative of the battle is at an inflection where only a few more collections of troops need to be overcome to declare their victory. Irrevocably: ‘The swarm is knocked into a cock straw hat.’33 Plath here seems to be driving and motoring the prosody to her own ends within the greater realm of the story of war; she warps the “swarm” itself – full of buzzing and hyper bees maintaining their energy and fight in battle – and brings them down, “knocking” them into a completely new and clear image; “a cock straw hat” is a significantly humorous image as Plath instils a more humane object and element to contrast the brawny and physical nature of warfare. The reference is a further historical item to the poem, describing cocktail straw hats; “Cocktail hats” are usually small, extravagant, and typically brimless hats, commonly a considerable symbol of feminine fashion. Most intriguingly for the narrative of the poem, the brim of these hats often have hairnets attached to them that drape down over the upper part of the face, with the string being sewn into equally small diamond shapes that help to distort and veil the face. Thus, the “swarm” of the bees have now been warped and shaped into the kaleidoscopic “swarm” of the hairnet of the hat; the hexagonal honeycomb made by the bees have descended and reorganised themselves into a multitude of diamonds as part of a “cocktail hat”. Furthermore, this brimless hat, not majorly in fashion nowadays, was often worn by women as an item of evening wear – intended as an alternative to a large-brimmed hat – and very popular from the 1930s to the 1960s; hence, we can confidently surmise that Plath has fast-forwarded us to her present-day (Sylvia Plath likely composed this collection of poems in the late 1950s and early 1960s), traversing stealthily, almost “buzzing like bees” into the future from the immensely bleak realm of the Battle of Waterloo. From the discussion of cocktail hats, it would be safe to assume we are now within the era of Europe leading up to and during the Second World War; Plath does not allow us to clearly escape “the swarm”, she merely continues to guide us swiftly through history and plunges us into another “swarm”; WWII. Plath rather mockingly berates the island of Elba once more as a demonstration of fervent opposition and uproar against Napoleon, going on to describe his officials and troops as ostensibly beaten and inadequate: ‘Elba, Elba, bleb on the sea! | The white busts of marshals, admirals, generals | Worming themselves into niches.’34 The Italian island of Elba that Napoleon ruled for ten months has become obsolete, to run parallel with Napoleon finally being defeated in military battle; it becomes a “bleb”, an unwanted blister in Napoleon’s long and tyrannical rulership that is threatened with its end once and for all; Plath skilfully calling back to Elba being a “hump” on his “short back”. “The white busts” of Napoleon’s “marshals, admirals, generals” profoundly mirror the whiteness of the ivory previously mentioned; the military officials having now been beaten, and now resemble inanimate, pale ivory figures. They finally “Worm into niches”, with the modal verb “worming” emphasising the slyness of Napoleon’s army being beaten, and eventually teased, so can only hide into hollow slits, or “niches”, to take refuge for their ominous last stand.

Plath continues in her sarcastically mocking voice to open the tenth stanza: ‘How instructive this is!’35 the playful tone she adopts here, for all its humour and jocularity, is a way of amplifying the significance of Napoleon and his Grand Army being defeated and the method in which it was done; the bees having caused immense damage and discomfort and brought “the swarm” crashing down to earth; thus it becomes an “instructive”, or educational outlet for future generations to look back and learn from; the teaming together of the Coalition nations having worked as a large and devoted group, which is one of the most prominent reasons why the Battle of Waterloo was swung and eventually won by Napoleon’s opponents. What is left of Napoleon’s army are now purely: ‘The dumb, banded bodies | Walking the plank draped with Mother France’s upholstery | Into a new mausoleum, | An ivory palace, a crotch pine.’36 The usage of the adjectival “dumb” is particularly hurtful from Plath to describe how feeble and ignorant the grand array of French troops, and Napoleon himself were to think they could come out victorious in this epic and decisive European battle, with the alliterative “banded bodies” being a further miserable signifier to the pale, ivory-imbued carcasses that have increased dramatically since the Coalition nations began to work like a “beehive” and swing the battle in their favour, while also literally describing the French soldiers’ and officers’ clothes, and the larger swell of “upholstery”, or furniture, as they have donned the blue, white, and red colours of the French flag throughout the long and protracted battle; the Tricolore ideals of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity having been fiercely attacked and turned on its head, the befallen men of Napoleon now dead, forlorn, and left to contemplate their military demise; the triumvirate phrasing of “Mother France’s upholstery” provides an added touch of sombreness and sentimentality as the effeminate nature of Napoleon’s own nation, having gained so much geographical area and political influence, is reduced to a fraction of its rich power and might; the “upholstery” transferred as cargo “Into a new mausoleum”. This incredibly bleak imagery instilled by Plath bares another cogent facet of historical dualism; it not only expresses the immediate consequence of Napoleon’s abdication following his and France’s defeat at Waterloo, – his grand Empire losing its stranglehold on world order – and all his associates, commanders and governors handing over their former ruler’s cherished furniture and possessions to the better side of history, but also quite demonstrably looks forward sullenly to the Holocaust; the fascistic ethnic cleansing by Hitler of the Jewish population having caused an implausible number of deaths in the Concentration Camps in Poland and Eastern Europe; and looking beyond the immeasurable life lost we as learners and witnesses to history turn to the free-standing, pale buildings of “mausoleums” that pay tribute to the millions of people who were innocently killed during the Third Reich; Plath therefore pays clear reference to a time of recent history for her personally, having been born just before the Second World War; the identification of a “new mausoleum” acts for her as a dual parallel, baring the weight of recent history with the widespread upheaval and destruction caused during the 1930s and 1940, and pins it to run alongside the lengthy and ruthless Napoleonic Wars over one-hundred years before. At the finale of this tenth stanza, Plath more or less completes the sorrowful portrait as the mausoleum becomes an “ivory palace”, baring a surfeit of white shade and a large, valuable building, that, for all its grandly luxurious appearance, the pale-white, absence of colour highlights a sense of a great void that has been created by historical and political forces; the idea that all-too-powerful regimes will corrupt their power, and use it to hideously cruel and corrosive ends, will potentially incite war and violence to achieve their aims; leaving behind a gross history whose monuments dedicated to them contain a voidness, a nothingness, for at their heart is evilness and human suffering. The final image of a “crotch pine” is exceptionally prescient, marking a small but remarkably creative flourish of Plath’s pen; the “crotch” forming in a pine tree is almost definitely referring to the deliberate cutting-off, or sawing off of the leaves and consequent blossoming of life on and within the tree; what is left is simply the hard and grainy trunk with a bifurcation of stubs pointing diagonally into the air; human life is emblematic of the pine tree, or trees in general. For Plath, in this context, so many lives have been lost to the man-made weapons used in war, thus the “crotch”, or fork in the tree is now representative of all the blossoming and growth of humanity being distinctly cut and wiped out to sizeable degrees, not knowing which way to look and build towards next. The allegorical punch of this stanza as a whole performs in a circulatory nature, as with the final image of the “crotch pine” clearly representing the crushing effects of war, we circuit back to the opening line: ‘How instructive this is!’, and are able to firmly reflect on this seemingly buoyant commentary from Plath; for is blood-spill and war really “instructive” after all? Maybe through our own coloured lenses, that see and consult what goes on everyday around us and across the world, in the infinitely larger swarm of life, we are to be true judges of that.

The Final Sting in the Tale

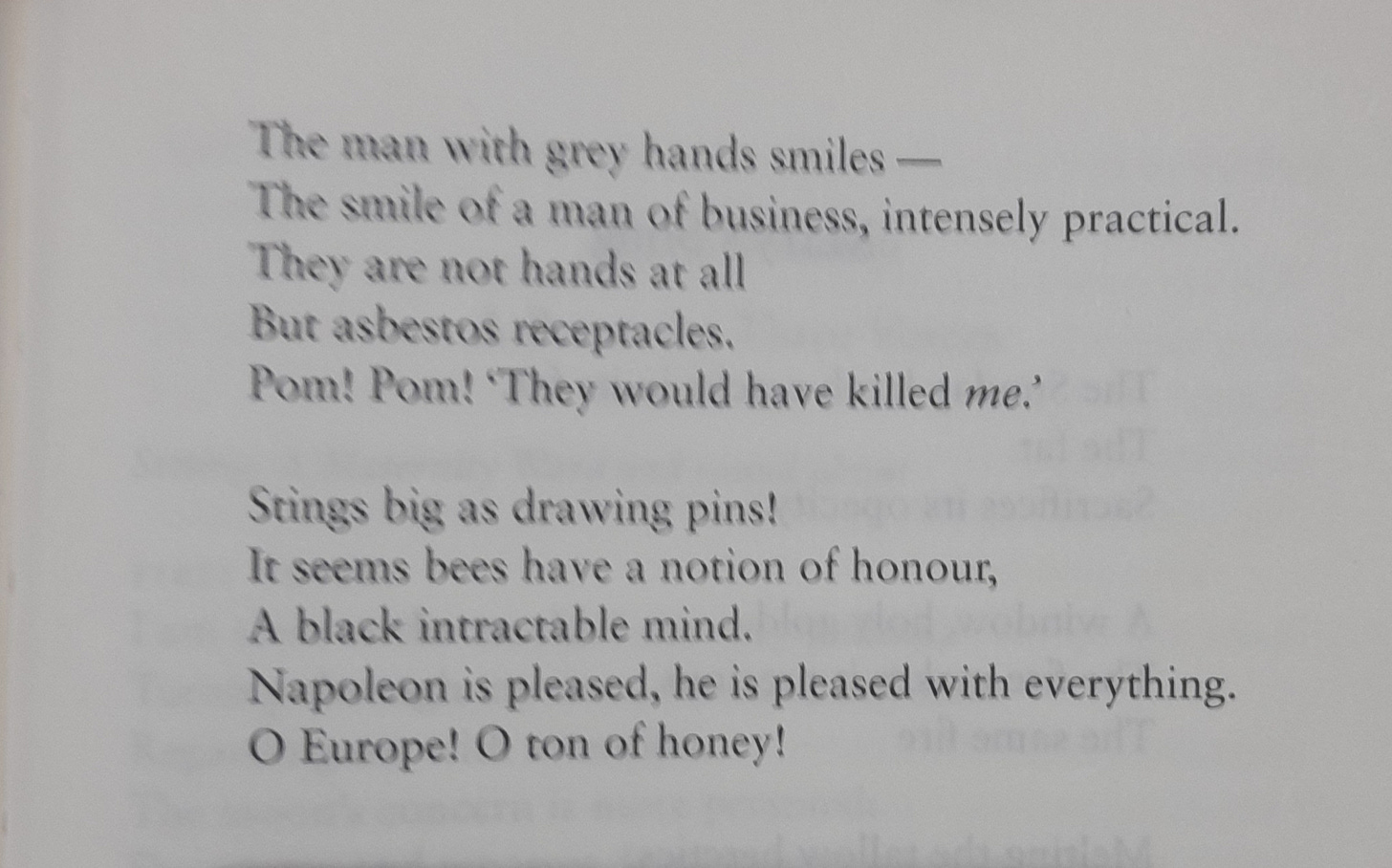

‘The man with grey hands smiles –’37, begins the penultimate stanza of this grand and sadistic swarm, with the extended dash/hyphen at the end being only the second occasion of its use from Plath, and first since the opening line of the entire poem. Likewise with “somebody shooting at something in our town –”, with the dash sinisterly corresponding to the lined gunfire of a gun, the “man with grey hands smiling” is a dark, leading image, having the propensity to represent numerous metaphorical pieces of human action, potentially morally ambiguous ones. “The man with grey hands” himself could likely be a random, lonesome figure within the large and devastating battle that has taken place who has navigated through the entire “swarm”; whether he was a member of the “beehive” that effectively confronted Napoleon’s army’s overwhelming threat, or whether he has been a more neutral person that has simply maintained his stance and fought through the bog and trenches of the battle, we do not truly know. Although, because of his “smiling” nature, it is probable that he is a wildcard of sorts, or “joker-in-the-pack”, that while he has not been mentioned regularly, and has behaved relatively docilely for the entirety of the conflict (“The man with grey hands stands under the honeycomb”), he has almost certainly been involved in the bleak or morally ambiguous activities of the opposing armies, in one way or another. Furthermore, the colour grey often represents neutrality or indecision, so “grey hands” suggest that the person’s actions are not clearly good or evil, but somewhere in between. The “smiling” element to his custom is potentially borderline sociopathic behaviour; he carries a profound sense of lifelessness or detachment from the carnage and death surrounding him; the “greyness” further being associated with dullness and lack of vitality. Consequently, the last dash “–”, written in after his smile, could symbolise his arm or skin, and that it offers a lack of human emotion, feeling, or sense of empathy and responsibility; it bares nothing but the skin of a person of deadness, perhaps, as Plath guides us menacingly to a more disturbing conclusion to the poem’s narrative. The four lines following the dash follow on plausibly, with the end of the stanza bringing in Plath’s first use of human dialogue: ‘The smile of a man of business, intensely practical. | They are not hands at all | But asbestos receptacles. | Pom! Pom! ‘They would have killed me.’38 We thus confirm that the “grey hand” man is more of a radical, virtuoso figure within the wider realm of the battle, “intensely practical”. It is in the vein of a hitman, or stout, macho figure being employed for immoral purposes to go and dismiss or kill an enemy, because the task is too delicate or difficult for the group to perform at large. Then, we receive the dramatic pummel from Plath, declaring that the “grey hands” of the man “are not hands at all | But asbestos receptacles.” An overtly comical remark that demonstrates that the man’s hands are tainted with poison and potential death; the “asbestos” being a potent silicate mineral that is used for industrial purposes, yet used frequently in the wrong way can lead to respiratory disease and fatality. The “receptacle” nature of his hands mean he has experienced, caused, and collected an array of murders and deaths within the battle, and for all the burning conflict and pain he merely maintains his “business” custom and mask. Plath at last intends to show that the man is human, in the boldly instinctive sense, and wants to remain alive, and fears death, even though he has likely faced it multiple times during the lengthy war: ‘Pom! Pom! ‘They would have killed me.’ The onomatopoeia of ‘Pom!’ at last acts as the man’s exhibition of his artillery, to show it as a crucial symbol of the swarm of life it has taken; that the noise initially being described as “dull” is in reality a firm and distressing sound; the man firing his gun twice before declaring he would have died himself are the final couple of bullets to signify the plainness and finality of bullets loudly firing and penetrating an object.

For the twelfth and final stanza of the poem, Plath upholds her fervent use of exclamation marks, perhaps acting as a significant sign of the anarchy and bedlam caused by the war and death that has happened through hundreds of years of history, and continues to occur during Plath’s day: ‘Stings big as drawing pins!’39 shows the impact of a “bee-sting” itself being in tandem with the might of a “drawing pin” piercing the skin; with drawing pins being gold painted, they mirror the “gilt” mentioned earlier regarding the Russian Empire and its appearance; as a consequence, while the drawing pins, or bee-sting pierce the skin to instigate its painful force, it is only temporary, which matches the “melting” and “burning” of the Russian “domes” and “gilt” descending to dust, yet will inevitably be rebuilt overtime for future generations to inhabit, whilst still ceaselessly baring the “stinging” scars of past enemies. With the wide metaphor of the “bees” maintaining their place until the ultimate ending, Plath provides a seemingly conclusive commentary on them; while they have been the energetic force that have risen to the bleakly threatened “black pine tree”, have “argued” amongst themselves in hordes, and formed a “flying hedgehog”, they are lastly described as key conformists to the war and destruction. Having trusted their frenetic ability to harry and hustle on the opposition side of Napoleon, it has been apparently easy for us to forget that they have been complicit players within the battle; the blood spilt and caused is also theirs; while the “honeycomb” is their item, and “honey” is their produce, have they for the most part just been submissive to the alluring greed of winning at war? Plath writes: ‘It seems bees have a notion of honour, | A black intractable mind.’40 This further supports our discovery to find the bees being participants in the swarming herd of warfare; a further emphasis of the many, many players that partake in war and are responsible for its consequences. The imagery of the “beehive” thus symbolises a society heatedly driven by aggression and conformity, while the threatening and visceral descriptions of the aforementioned objects and weapons (“bullets, beak, claw, ivory”) and the “Pom!” of the gun plainly represents the destructive force unleashed by them. The bees’ “black intractable mind” personifies their stubbornness and lack of will to turn back on their intentions once they have entered a scene, namely the larger swarm of the battle. The final two lines of the poem come as cutting and sulkily portentous declarations of Napoleon and his Grande Armée coming to the fore once more, for while they have been toppled in the rustic swell of land of Waterloo, all the vast ranges of opponents from Britain, Germany, Poland, Russia etc. have sacrificed a gigantic number of their populations to try and win this singular grand battle of history. The bees come swarming in again, this time more ominous and troublesome, buzzing and murmuring over the evident devastation and casualty that lies in “tods of ivy” of the land: ‘Napoleon is pleased, he is pleased with everything. | O Europe! O ton of honey!’41 The finalising, exclamatory description from Plath of Europe baring the image of a “ton of honey!” all but establishes our acceptance of the blood spilled; learning of it as a cruel inevitability melds with the eerily oozing image of a mass of honey swarming the land, merely basking viscously atop the ground and showing the dismal produce of all the bees’ effort at the last.

Ultimately, Plath’s ardent use of historical inferences and references to Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars is a horrific and heavy collective symbol for the extensive ruin and turmoil that war creates. The bees arriving in their droves and hustling in forceful number to try and palliate the damaging effects of warfare across a grand scale eventually become an important portion to the problem of war; its players come from all areas, directions, and walks of life; whether from the North, East, South, West, Christian, Jew, Atheist, Calvinist, Socialist, or Ecologist, it does not matter across the larger sphere when they all will sooner or later take part in and become responsible in a minor or big way for the inevitable outcomes that war necessitates. Compared to other works of Plath, The Swarm shares her common themes of violence, loss, family, partisanship, and the harsh effects of war, but at its core it incorporates a distinctive allegory to convey what happens when people in positions of power allow war to endure through time, unevaded.

Sylvia Plath, Stopped Dead, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 16, i-ii

Sylvia Plath, Stopped Dead, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 16, xviii-xxii

Sylvia Plath, The Rabbit Catcher, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 17, i-ii

Sylvia Plath, The Rabbit Catcher, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 17, xi-xiii

Sylvia Plath, The Rabbit Catcher, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 18, xxvi-xxx

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, i

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, ii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, iii-v

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, vi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, vii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, viii-x

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xiii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xiv

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xv

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xvi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xvii-xviii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, ixx-xx

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xxi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 31, xxii-xxv

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxvi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxvii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxviii-xxx

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxxi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxxii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxxiii-xxxv

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxxvi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxxvii-xxxviii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xxxix

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xl

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xli

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xlii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xliii-xlv

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xlvi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 32, xlvii-l

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 33, li

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 33, lii-lv

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 33, lvi

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 33, lvii-lviii

Sylvia Plath, The Swarm, in Winter Trees, (London: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971), p. 33, lix-lx